Rafah Refugee Camp, Public Eye, May 19, 2004 At least ten Palestinians were killed and 35 wounded when Israeli forces fired on a crowd demonstrating against the invasion of a Rafah refugee camp today.

Builders and Warriors / Scenes of Military Urbanism from the Colonial Frontiers

If until after the modern period cities were taken upon the breaching of their outer walls and therefore surrounded themselves with complex system of perimeter fortifications,

current wars take place within the city's “soft” fabric,

amongst the relics of daily life, merging the science of urbanism and that of war. The fight is for the city itself, with urbanity no longer only the locus, but the very apparatus with which wars are fought.

With their tendencies to density, sprawl, congestion, heterogeneity,

formal diversity, multi dimensional structures, subterranean

infrastructure, electromagnetic interferences, and radio wave clutter urban areas are hard to invade, difficult to hold and near impossible to police.

US military planners fear that the enemies defined by estern

powers – insurgents, terrorists, street gangs and criminals

of all kinds and sorts may effectively set up extraterritorial

enclaves within what the future battle ground will inevitably

continue to be – shantytowns, refugee camps, Kasbahs and the other so called “bad neighborhoods” that seem to proliferate across a rapidly urbanizing world.

|

Israeli Engineers in Tul Qarem Refugee Camp, Nir Kafri, 2003Israeli Engineers in Tul Qarem Refugee Camp, Nir Kafri, 2003

In the frictions of a rapidly developing and urbanizing world, human rights are increasingly violated by the organization

of space. Just like gun or the tank, mundane building matter is abused as weapons with which crimes are committed.

From the political/military point of view, the city is a social/physical obstacle that must be reorganized before it can be controlled.

“Design by destruction” increasingly involves planners as military personnel in reshaping the battleground to meet strategic objectives.

The destruction in Bosnia of public facilities – mosques, cemeteries and public squares – followed a clear and old fashioned planner's logic: social order can not be maintained without its shared functions. |

|

The manipulation of key infrastructure – roads, power, water and communication, such as in Baghdad – seeks to control an urban area by disrupting its various flows. Bombing campaigns

rely on architects and planners to recommend buildings

and infrastructure as potential targets and in order to evaluate the urban effect of their removal. The destruction of monuments and heritage sites, such as in the bombing of Belgrade, seeks a psychological victory over “enslaving”

architectural projects. The grid of roads, the width of an army bulldozer, that was carved through the fabric of the refugee camp of Jenin and the “clearing out” of a large empty area at its center reveals another planners' specialty – the replacement of an existing circulation system with another – one more accessible to the occupying army and easier to control popular unrest in. |

|

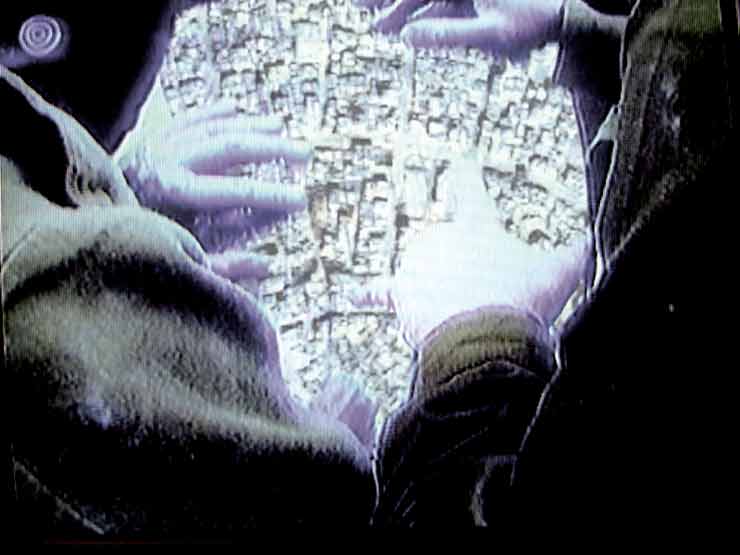

The Urban Terrain, Doctrine for Joint Urban Operations, Prepared under the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Lieutenant General John P. Abizaid, 2002. “In fully urbanized terrain,” Ralph Peters writes, “warfare becomes profoundly

vertical, reaching up to towers of steel and cement, and downward into sewers, subway lines, road tunnels, communication

tunnels, and the like”. (Quote and image courtesy of Steve Graham)

Military Urban Academies

Battles in this urban-terrain will be lost or won, according to the military with the ability to re-organize, in effect re-design, the urban environment.

To help the military must think (and act) in planning terms, as geographers Simon Marvin and Steve Graham show, the military

have launched such well funded, equipped and manned urban research programs that they seem to currently surpasses all urban research done in the civilian sphere, that is rivaling all universities and graduate schools combined!

Soldiers, which are the urban practitioners of today, take crash courses in urban infrastructure, complex system analysis,

structural stability, building techniques, and even in some rudimentary forms of urban sociology.

A publication titled Doctrine for Joint Urban Operations released by the US military divides cities, like much else in the military, into three composite parts that it terms the “urban triad”. |

|

The first includes physical structure – buildings and roads. The reorganization of these by force typified urban conflicts at the 19th century with their acts of Haussmannization, and still represents a large component of urban warfare today.

The second part is urban infrastructure. By temporarily shutting down electricity and telephone connections in particular

parts of a city, the military believes it can paralyze its defense without having to be physically present.

The third component is the urban population itself. Through what the US military calls in rather Orwellian terms “strategies for reprogramming mass consciousness” or Psychological Operations [PSYOP], the urban population is manipulated to perform what is in effect military interest. “Cultural intelligence” attempts to uncover the social fabric of a city and the way it relates to the built fabric, as well as the logic of social groupings, local politics, and local rivalries,

in order to take full advantage of them. |

|

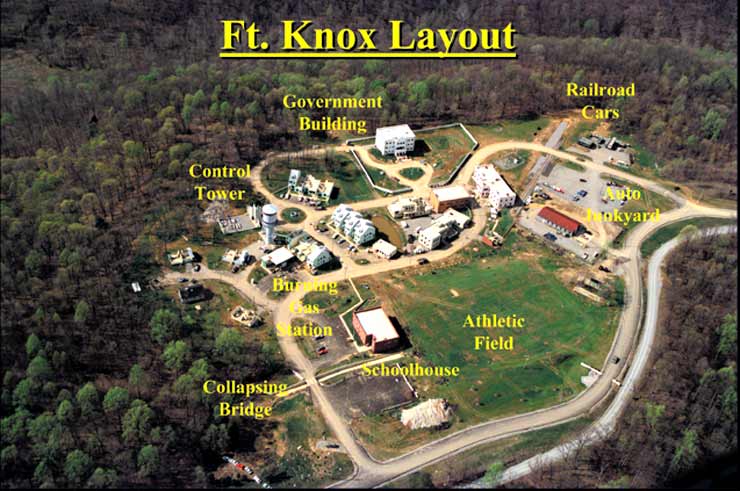

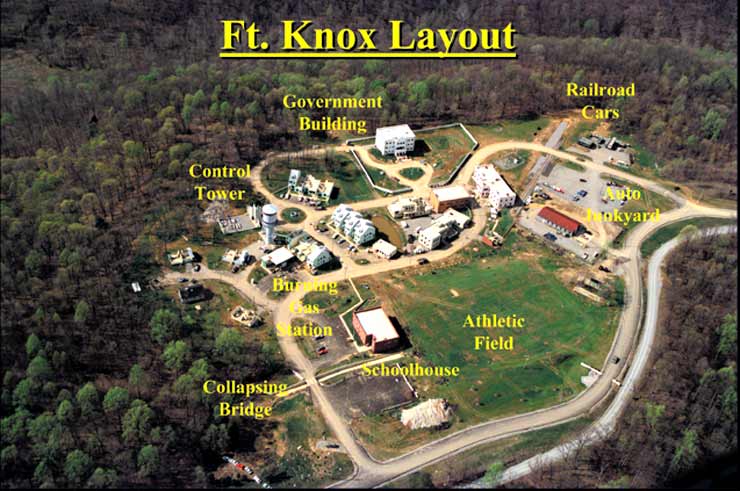

The Mock-Up City at Ft. Knox, Maine core urban warfare training ground, Seth Bokmeyer, Urban Warfare conference, SMI, London 2002

Training

A number of facilities were built to allow training of urban warfare. Derelict inner city neighborhoods and newly built mock villages and towns allow militaries to simulate warfare in cities, refugee camps and slums. Sometimes film-directors are brought in to imagine scenarios for the military to tackle. In order to make training realistic, soldiers, actors and sometimes even prisoners are brought in to simulate urban crowds, recording of urban life, the sounds of jets and gunfire,

and the combination of smells of cooking, decomposing bodies, sewage and stagnant water are released throughout the “town”.

The IDF has established the “academy for urban fighting” in the Negev desert, where obscured from view by mountain ridges, the biggest Arab mock-up town since Ben Hur was built. The town is large enough to include areas that resembles city centers and others resembling refugee camps. It has been given the name “Chicago” in homage of another bullets riddled town.

The US military regularly trains there before being assigned to Iraq |

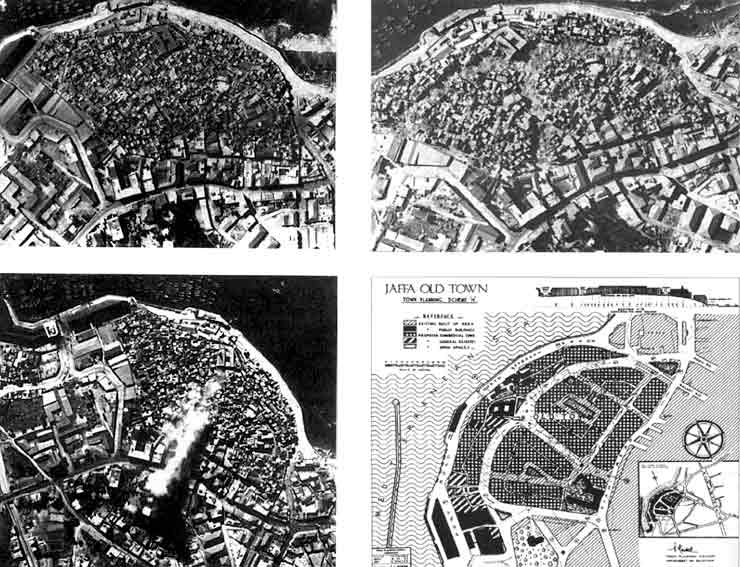

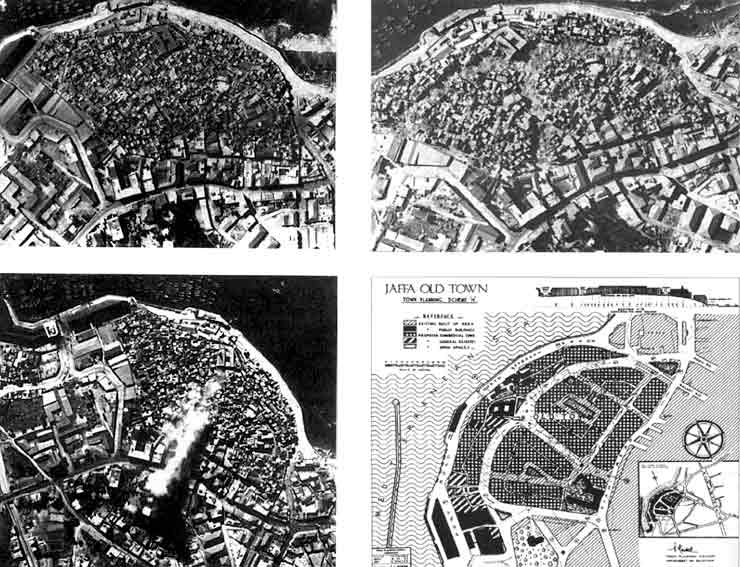

Operation Anchor, Jaffa, 1936, Royal Air force

“Design by Destruction”

In the 19th century, two kinds of “design by destruction” can be identified: while urban warfare is tested at the periphery of the Imperial domains, where the dense oriental cities were seen as filthy and decadent, the modernization policies in the overcrowded European cities of the industrial revolution employed similar tools, but camouflaged themselves with different rhetoric.

The tandem of modernization and urban destruction was carried into the 20th century in many corners of the colonial

world. In Palestine “Operation Anchor”, a “designed” destruction of Old Jaffa, was carried out by the British forces in 1936—a time later known as the first Arab rebellion—

perhaps the first Intifada. British forces suffered casualties from “saboteurs” based in the “internal fortresses” barricaded within the old inner city.

As part of a large-scale policy of demolition that saw some 2,000 Palestinian houses destroyed between 1936 and 1940, the British Mandatory Government decided to cut a large anchor-shaped boulevard through the old city in a way that would make the erection of barricades impossible. |

|

The royal air force dropped evacuation orders from the air, allowing few thousand Arab residents twenty-four hours to evacuate. The British military later detonating between 300 and 700 homes.

When concerns were voiced in the British Parliament about a possible bias of the government against the Arabs, the destruction was defended as urgent measures of regeneration and public hygiene in an area lacking basic services. Indeed soon after the destruction, infrastructure began to be laid out under the path of the ruins.

Submitting the Arab Kasbah to the logic of maneuver and speed, the anti urban attitudes of the British military have paradoxically drawn the blueprint for a modern city, inspiring

such future practices of modernization, classification and hygiene that attempted to “merge city and countryside”, by denying the basic heterogeneity density and conviviality that are the basic characteristics of urban live. |

|

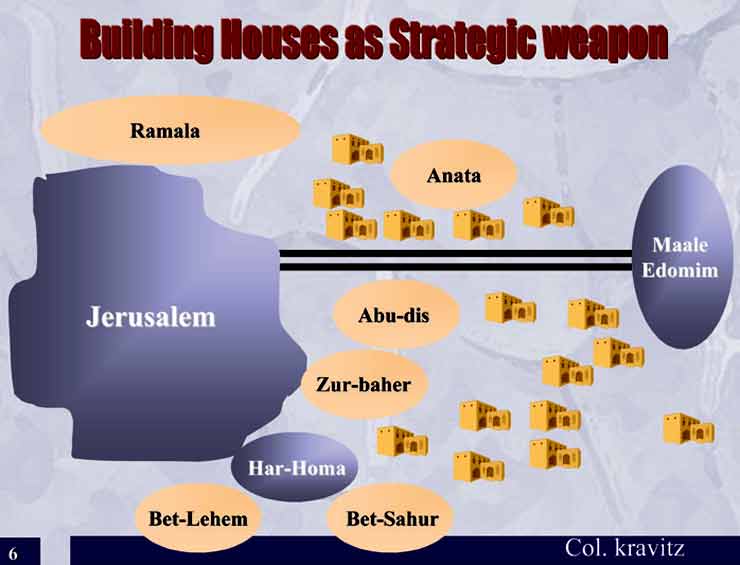

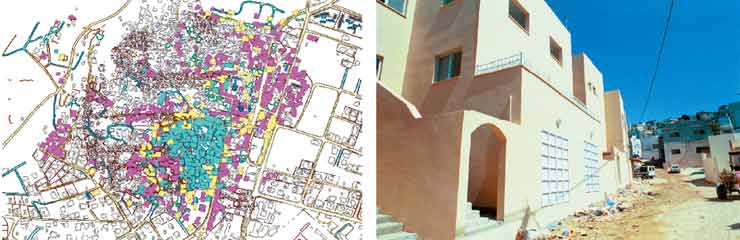

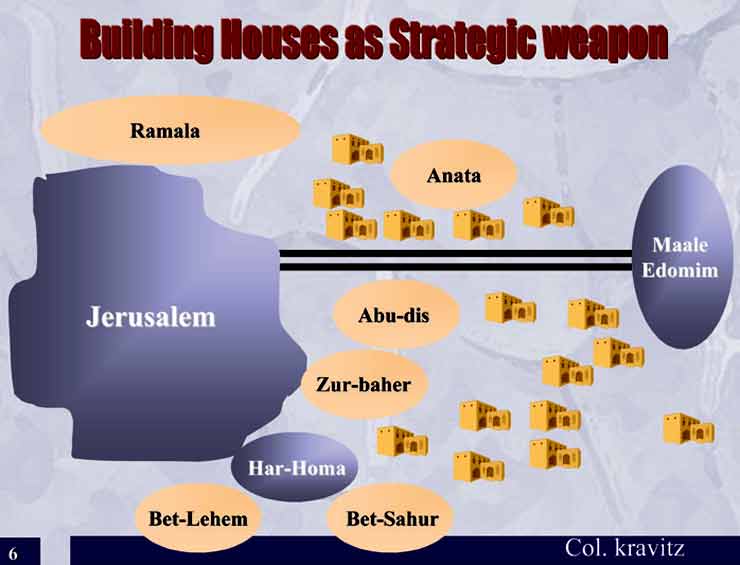

Building Houses as a Strategic Weapon, Col. Moshe Kravitz Slide from a lecture, “The Post Cold-War Era MOUT Operations, IDF Experience”, delivered at the conference 'Urban Warfare' , SMI, London December 2002

Architecture as a Weapon

During the years, Israel gradually came to view its armed conflict with the Palestinians as an urban problem, and the rapid expansion of the refugee camps as the “Jihad of Building“, that needs to be tackled by directly transforming the very “habitat of terror” – the urban fabrics of the refugee

camps. In the following years, regional and urban planning

became instruments of a militarized campaign against the Palestinian urbanity. Israel still sees the control of the West Bank's fast-expanding, complex and interconnected refugee camps an essential component that may secure Israel's control over Palestinian politics and resistance.

The way to contain the threats of an “uncontrolled Palestinian Urban sprawl” was by using the weapon of counter-urbanity – or more precisely, sub-urbanity. From the 1980s onwards, Israel was using settlements as an antidote

to uncontrolled Palestinian population growth, placing them as wedges that disturb the consolidation of large metropolitan

centers – those most likely to form the cultural demographic and political basis of a viable territorial entity. |

|

While Israeli planners prohibits the expansion of the refugee camps by tight zoning laws, and places settlements to physically

blocks their expansion, the IDF regulates the camps' internal fabric by periodic destruction in campaigns of urban warfare, and periodic proposals for resettlement.

Ariel Sharon, Chief of Southern Command in charge of Gaza in 1971 seemed to have picked up on colonial methods of “pacification” and counter insurgency, when he ordered a rectangular grid the width of an army bulldozers to be cut through the dense fabric of the otherwise pedestrian alleyways

of the refugee camps, destroying or damaging some 6,000 homes in the process.

This brutal chapter in the history of the grid was to inaugurate

the IDF practice of “design by destruction”. |

|

Eyal Weizman clarifies: The image attributed to Nir Kafri, 2003, previously posted here, was erroneously changed from the original and was subsequently removed.

A Laboratory of Urban Warfare

On 29 March 2002 the IDF launched “Operation Defensive Shield” – an offensive whose stated aim was the dismantling

of the “infrastructure of terror” responsible for a series of suicide bombing within Israeli cities. The operation was played out within Palestinian urban environments of different characteristics – a modern city with modern infrastructure and some mid and high rises in Ramallah, a dense historic city center at the Kasbah of Nablus, an international holy city in Bethlehem and refugee camps in Jenin, Balata and Tul Qarem. The operation has thereafter become a laboratory for emerging new tactics of urban warfare.

As long as fighting took place between the homes and streets,

small groups of Palestinian fighters moving in the lower stories

were Israeli helicopter fire could not reach through tunnels

and secret connections, managed with sporadic skirmishes to

hold back 4 IDF division. Fighting occurred within the ruins

of daily life, between wreckage of furniture, home electronics

and kitchen utensils. Soldiers and defenders shot at each other

through holes blasted through walls. |

|

In an interview, shortly after battles, an Israeli reserve soldier described thus the first days of the battle. “It was a complete chaos, nothing like our training, nothing we could expect…everything happened together from all sides.”

On both sides civilians turned combatants, and combatants turned

civilians again. Identity changed as quickly as gender appeared

to be, characters switched from women to fighting men in the

speed it takes an undercover “Arabised” Israeli

soldier or a camouflaged Palestinian fighter, to removes a machine

gun from under a dress. “For us” the soldier continued

to tell “it became impossible to draw up scenarios, plan

what to do, or draw up single-track plans to follow through.”

Indeed as far as the military is concerned, urban warfare is

the ultimate post-modern war: beyond the ambiguity of characters,

the belief in a logically structured, single-tracked and pre-planned

approach is lost in the complexity and ambiguity of the urban

reality. |

|

IDF D9 Bulldozer marks a line of no entry, operation “Defensive Shield”, April 2002 images by an anonymous Palestinian

activist

Destruction of Jenin

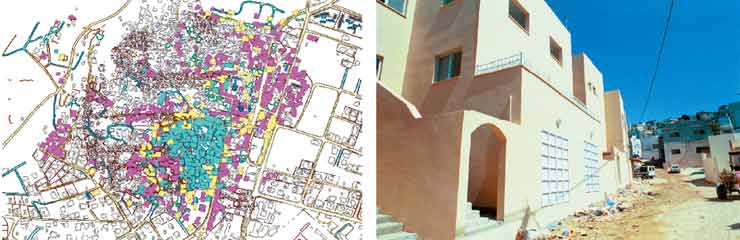

The complexities of urban warfare were erased in the last days of the battle of Jenin when bulldozers collapsed the entire center of the refugee camp – an area of about 40,000 square meters – on its defenders and some of its residents.

The battle completely transformed the urbanity of the camp, making wheeled maneuver near impossible. Continuous rocket fire and shelling by the IDF gradually cumulated building into a sharp topography of broken concrete and glass sprouted with twisted metal bars. The hills of rubble were honeycombed with cavities of buried rooms. Within this lunar landscape, civilians and fighter were mixed in un-oriented movements.

Destruction however was not arbitrary but followed an inherent military logic. The IDF used armored D9 bulldozers to break paths through built fabric of the camp “widening” narrow alleys and carving through the topography of rubble. Along these paths tanks and other military vehicles could penetrate deep into the camp's interior. |

|

Each of the bulldozers was manned by a crew of three, and commanded by an engineering officer, usually a civil engineer

or an architect on reserve duty. These professionals were essential to direct demolition work, decide which structural

columns to tackle and to which direction the building should best be toppled. An Israeli engineering officer that lectured in a recent military conference mentioned that in contrast to the battle of Jenin “these days, helped by the study of building construction and structures the military can remove one floor in a building without destroying it completely

or remove an building that stands in a row of buildings

without damaging the others.”

At the end of the battle it became apparent that fifty-two Palestinians were killed, more then half of them civilians, some buried alive under the rubble of their homes. Three hundred and fifty buildings, mostly homes, were destroyed, further 1,500 were damaged, and about four thousand people were left homeless. |

|

Jenin Refugee Camp after the battle of April 2002

Blue squares denote completely demolished buildings

Red square denote partially damaged buildings

The Refugee Camp of Jenin, Israeli Air force, , April

2002

New Route Cut through the urban fabric of the Refugee

Camp of Jenin, image by anonymous Palestinian activist, April 2002 |

|

New Homes built by UNRWA to replace the destroyed

homes in the Refugee Camp of Jenin, Miki Kratsman,

June 2004

When funds from the United Arab Emirates allowed

UNRWA – the United Nations Relief and Works Agency

– to replace most of the homes destroyed during the opera-

tion with modern buildings, UN architects, internalizing the

brutality of the logic imposed by IDF operation of “design

by destruction”, decided to allocate some 15 percent of the

original lots of destroyed homes to widen the roads to allow

Israeli tanks to access the camp without having to break

through the homes again. |

|

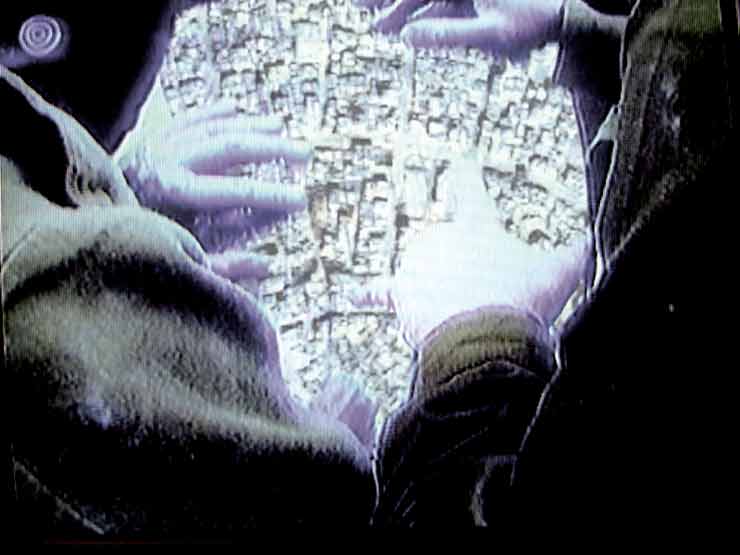

Israeli Infantry in Tul-Qarem refugee Camp, Israeli Channel One, April 2002

Swarming

According to Aviv Kochavi, the officer in command of the battle of Balata refugee camp on April 2002: “The IDF would stealthily enter the camp from several directions, move through alleys, cracks, walls, fire four bullets here, ten there…and move to another position before being spotted…”.

In contrast to linear operation where military column progress

gradually from outside in, securing the axis as they move on, “swarming” organizes attacks from the inside out, changing directions, moving in zig zags so defenders may find it hard to predict the attacker's next move. In theory at least, a “swarming” force “has no form, no front, back or flanks, but moves like a cloud” and should be measured by location, velocity and density, rather then power and mass.

While the traditional military strategies are linear in the sense that they follow a determined, consequential sequence of operations, in which a series of military solutions add up to form a complete battle plan, warfare in the urban environment,

demand a complex simultaneous, unexpected and non linear approach. Although all actions are deterministic in principle, they are highly sensitive to minute irregularities, in a way that interferes with the ability of the military to form a coherent “battle plan”. |

|

The single-track narrative of the clockwork battle plan is replaced with a non-sequential approach of the tool box.

The “tool box doctrine” demands that soldiers receive the appropriate tools (weapons, ammunitions or apparatus) to deal with a series of emergent situations, but not know the order in which these events would occur.

The military thus keeps a flexible ability to fight without a proscribed sequential plan. |

|

Israeli Infantry in Tul-Qarem refugee Camp, Israeli Channel One, April 2002

Self Organizing Systems

Employing a the “swarming” tactics the military claims to adapt itself to the complex nature of cities, to use the chaos and the non-linearity of the urban environment to its own advantage.

The physical cohesion and hierarchical organization of militaries is replaced with a decentralized non-hierarchical

command and control system. A multiplicity of small, coordinated, autonomous forces, are organized in loose command

network, each unit given the possibility to act with high initiative and responsibility so that the result is a “self organizing” system that is able to deal with singularities on a local basis without burdening the chain of command of rigid hierarchical, top-down operations. De-centralized operations might seem like “organized chaos” but are in effect self-organizing, complex systems whose patterns replicate themselves

like fractals on every scale.

To a large extent, the “swarming” tactics is nothing but a high-tech version of Mao's second stage of liberation war where coordinated guerrilla action, complete with well timed concentrated attacks, camouflaging tactics, and deep penetration

replaced already at the early years of the last century, linearity with simultaneity. |

|

Synergy between highly dispersed semi-autonomous units is seen as a force multiplier and is achieved through the real-time sharing of information. The synergetic integration of air and ground forces allowed every unit commander to receive information from all available sources. Israeli soldiers were using their personal handheld mobile phones to coordinate

operations. Similarly, Chechen fighters in Groznyy were coordinating attacks on Russian troops with Russian networked mobile phones. Palestinian fighters were using mobile phone during battle, until they realized that an open hand held phone transmits radiation that gives away their location and is usually followed by a GPS guided bomb. |

|

Israeli Infantry in Tul-Qarem refugee Camp, Israeli Channel One, April 2002

Moving through Walls

Swarming requires an ability to move fast and unexpectedly across

all dimensions of the city. What the military terms as “Inverse

geometry” is in effect a re-organization of the urban syntax

by the movements of infantry soldiers. Moving sideways across the

width of alleys soldiers were cutting “free” paths through

walls between adjacent homes and tunneling their way like worms across

“solid” urban fabric.

As a physical transformation and material reorganization of city syntax, “warming” allows for free, three-dimensional movement through the solid fabric of the city. Soldiers traveled

through walls, from one home to the next, cutting openings

with hammers or explosives, making connections that were unapparent and unexpected to the defenders.

Seeing and moving through walls has been defined by the military as the indispensable condition, the absolute prerequisite

of the urban warfare today. Indeed, special facilities and equipment are employed in order to break through this most absolute given of architecture. Based on technology

that resemble ultrasound, wall surveillance radars are designed to provide a high-resolution three-dimensional renderings

of the entire room behind the wall. Special ammunition

will pierce through reinforced concrete walls without deflecting or even changing their trajectory, gradually rendering

all architecture transparent. |

Left: Temporary Fortifications, The Green Zone, Baghdad right: Flags in Belfast, Israeli flags are used often by unionists whereas Palestinian flags are used by republicans, reproducing the Israeli Palestinan conflict within Northern Ireland. Photograph: (need to find)

Mimicry and War

Militaries “learn” from each other through direct transfer of information, but as well through replicating and reproducing techniques exposed in open channels.

The “Shiite Intifada” currently unfolding in Iraq, seems to be part of a whole imaginary geography that has seen the “Palestinization of Iraq”, by which the Iraqis were Palestinianized, as much as the American military was Israelianized. Israeli technology and skills especially in the realm of Urban Warfare are transported from the West Bank to Iraq. US military was present in the West Bank during the battles of “Defensive Shield” learning from Israeli experience and transporting this knowledge to Iraq.

Thus the wall around the American compound in Baghdad looks as if its components are leftovers from Jerusalem, acts of urban destruction take place in Faluga, Swarming techniques

in Baghdad, “temporary closures” are imposed on whole towns and villages with earth dykes and barbed wire, larger regions are carved up by roadblocks and checkpoints, homes of suspected terrorists are levelled, and “targeted assassinations” are reintroduced into a new militarized geography. The reasons for this is not only because these have become parts of a joint military curriculum written by Israeli training officers, but because conflicts spread out by a process of mimicry, at whose centre the West Bank functions

as a laboratory of the extreme. |

|

| Explosive belts, razed buildings, road blocks, and assassinated

leaders thus float within common channels of news report and internet sites, and replicate themselves without the need for a precise tutorial or a direct order. |

|

|